Introduction

Youth offenders aged 15–24 years account for 40% of criminal justice apprehensions despite comprising only 15% of the population, with individuals aged 17–24 years offending more than any other age group (Lambie, 2018). Given that the adolescent developmental period continues until the mid-20s and their executive functions are still developing (Lees et al., 2020), adolescents have not fully developed cognitive abilities such as impulse control, awareness of the consequences of their actions and psychosocial maturity. This is of particular concern in the youth forensic population because of the higher percentage of exposure to biological, psychological and developmental factors that impact cognitive development compared with the general population.

Traumatic brain injury, trauma and neglect, mental health presentations, exposure to alcohol and recreational drugs in gestation, polysubstance use, intellectual disability and neurodevelopmental disorders are prevalent in forensic populations. These factors impact cognitive functioning and development of executive functions, information processing and memory (Cyrus et al., 2021; Faedda et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2018; Lees et al., 2020; Molitor et al., 2019). They also have a secondary impact on an individual’s capacity to engage in rehabilitation interventions and transition from the highly structured and routine based prison environment to function in the community. Such impacts were demonstrated by Syngelaki and colleagues (2009), who found that in a group of youth offenders aged 12–18 years, estimated IQ scores were lower than the general population and perseveration in responding was higher. These youth also had specific impairments in areas such as problem solving, working memory and planning. Barnfield and Leatham (1998) found that in a sample of 50 male prisoners in New Zealand, all participants performed below population norms on verbal memory and abstract thinking, with identified differences attributable to severity of TBI or level of substance use.

Neuropsychological assessment is an important tool that provides an in-depth understanding of an individual’s cognitive abilities and helps shed light on the causation of cognitive impairment. The process involves gathering comprehensive medical, academic, psychiatric and developmental histories for an individual through interviews and reviews of medical documentation. To gain an understanding of cognitive abilities, an assessment is completed with a variety of tasks that measure memory, attention, processing speed, reasoning, judgement, problem solving, spatial skills and language functions (Harvey, 2022).

Research on the implementation of neuropsychological services has continued to show benefits for functional outcomes, diagnostic clarification, understanding strengths and weaknesses, effective rehabilitation planning, prediction of long-term daily life outcomes and recovery of function (Arffa & Knapp, 2008; Bennett, 2001; Donders, 2020; Harvey, 2022). In Australia, Allott and colleagues (2011) explored the perceived utility of neuropsychological assessments in an adolescent mental health setting. Their results demonstrated that referrers perceived the neuropsychological service as highly useful and this service led to changes in clinical practice and clinically meaningful outcomes. That study also indicated neuropsychological assessment led to diagnostic changes or additions (11% of clients), changes to approaches in treatment (52% of clients) and increased or appropriate access to services, education or work (33% of clients). Referrers also reported that almost 60% of neuropsychological assessment reports were forwarded to other services or clinicians involved in clients’ care.

Research into the cost-benefit of neuropsychological assessment is limited despite a wealth of qualitative research demonstrating ongoing gains such as functional outcomes and perceived increased engagement with support services. These findings suggest the likely cost-benefit for Corrections with the potential for reduced recidivism following more tailored intervention and referrals to services adapted to cognitive difficulties. A study involving US veterans demonstrated a clear cost-benefit from neuropsychological assessment for the healthcare system, where a reduction of hospital service use followed neurological evaluation (VanKirk et al., 2013). In that study, assessments were completed for 440 US veterans, and within subject comparisons showed reduced incidence of hospitalisation and length of stay. Other research suggested impaired executive functioning predisposed recidivism in first-time adolescent male offenders, thereby suggesting a greater need for support services (Beszterczey et al., 2013; Miura & Fuchigami, 2017). Improved understanding may increase targeted programmes for those with cognitive difficulties. Rowlands and others (2020) demonstrated improvement in cognitive abilities among those who received a targeted cognitive intervention in a population of incarcerated adolescent males.

Education regarding cognitive functioning (e.g. impaired memory, slowed information processing) means staff can be trained to recognise key behaviours as signs of potential cognitive disability rather than defiance or insubordination (Yuhasz, 2013). This was exemplified in a New Zealand report as follows.

Data must […] guide better workforce planning of skilled staff and organisational responses so that prevention and intervention are effective, for risk identification without collaborative, skilled and wide-ranging community and government response is likely to be inadequate. Adequate investment is needed in piloting and evaluating early intervention and prevention initiatives to ensure evidence-based, cost-effective programmes are implemented. (Lambie, 2018, p. 24)

There is limited research regarding the use of neuropsychological assessment to inform practice and interventions in a youth forensic setting. Therefore, the aim of this study was to complete a thematic analysis of interviews focusing on report use following completion of neuropsychological assessments of young men in two youth forensic settings. The interviews explored the process of how neuropsychological reports were used and informed practice. Based on previous research in healthcare settings, it was hypothesised that the reports would assist in increased understanding of youth presentation and diagnostic clarification that would lead to changes in practice. Furthermore, it was hypothesised that neuropsychological reports would inform appropriate referral pathways and increase funding opportunities for suitable services for these young men.

Methodology

Ethical Approval

This study was reviewed and formally approved by research ethics committees from both Ara Poutama Aotearoa (NZ Department of Corrections) and Oranga Tamariki (NZ Ministry for Children).

Procedure

From July 2020 to December 2021, 70 neuropsychological assessments were completed for young men aged 14–21 years residing in two youth justice residential facilities. As part of a review and audit process following completion of the project, staff working with the young men were invited to complete an interview to explore the impacts of providing a neuropsychological service assessable to all youth in the youth forensic setting.

Staff, including educators, case leaders, case managers, medical staff and principal corrections officers, were contacted via email and invited to complete an interview. A list of interview questions (Appendix I) and a consent form were provided in the email. Participants could choose to respond to the questions in a written format, or complete a telephone or face-to-face interview. Interviews were completed with 15 staff who expressed interest in this study and consented to the interviewing process. The interviews were then transcribed.

Thematic analysis was performed as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). A quantitative analysis of neuropsychological report utility was not undertaken as it did not adequately capture the impact of neuropsychological assessment because of the complexity of the settings and differing individual factors. Reflexive thematic analysis was selected as it offered the possibility to gain a rich and in depth understanding of the possible impacts of neuropsychological assessment in youth justice and could yield both descriptive and interpretive accounts of the data. The epistemological stance of tempered realism was adopted for this study. Although a broadly uncomplicated relationship between language and reality was assumed, the authors were aware that researchers and participants would impact one another, and the authors’ values and assumptions would contribute to both the questions asked and interpretation of the data. It was therefore important that the researchers’ reflected on their subjectivity and how this impacted data collection and the perception of data collected. The analysis was conducted using an inductive ‘bottom-up’ approach in which there was no attempt to fit the data to an existing theory (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

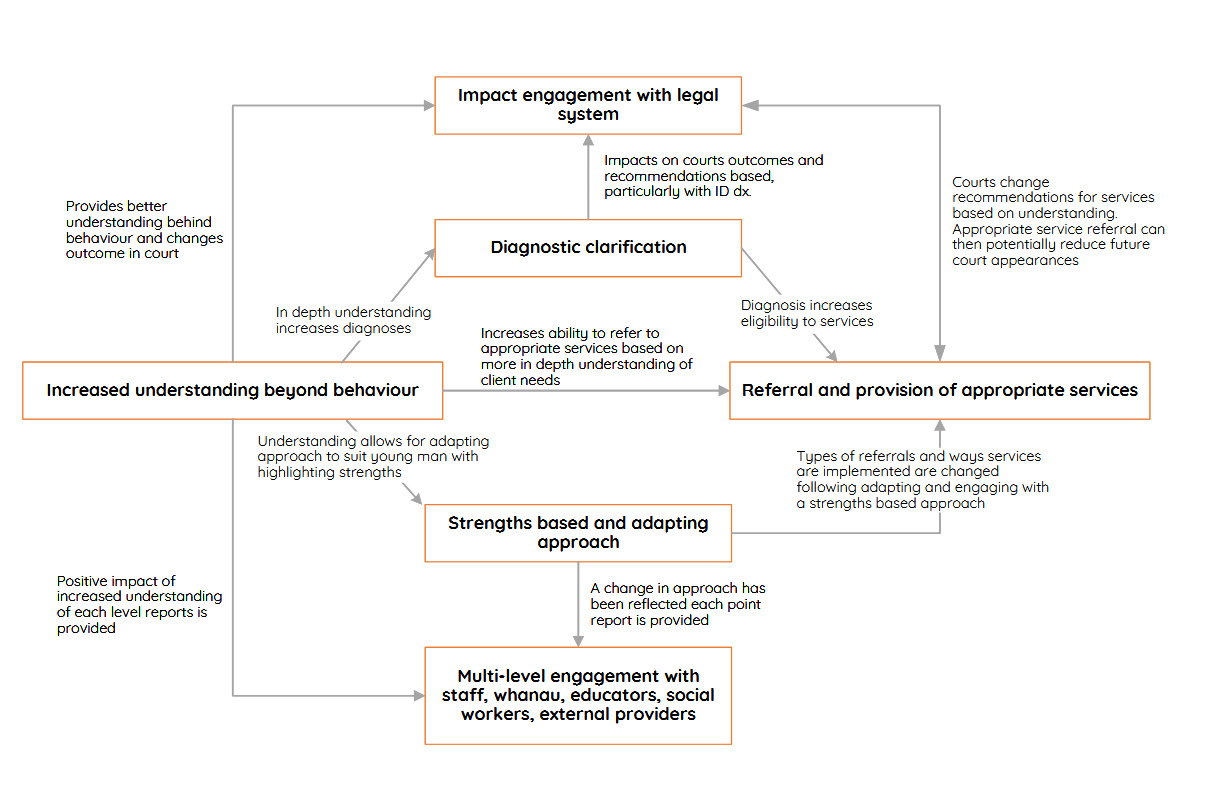

The interview transcripts were reviewed and coded to identify main themes, with patterns across codes identified focusing on how the reports were used and of benefit. A six-phase thematic analysis was undertaken to explore patterns across the dataset (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The six phases were distinct, but allowed a flexible approach between phases. Electronic copies of the data were reviewed over multiple time periods and different environments to enable new reflections, interpretations and perspectives on the data. Themes were reviewed and those that did not relate to the central theme of neuropsychological report utility were discarded. The initial review generated hundreds of codes, which were clustered into nine main patterns of meaning covering referrals and access to services, increased access to neuropsychological services, legal system engagement, diagnostic clarification, increased understanding, strength-based approach, adaptation and changes of approach, multi-level engagement, and barriers of confidentiality. Themes and definitions were then generated from the codes and a thematic map was created to illustrate the connections between themes. Codes, themes and definitions were reviewed by another researcher before being finalised.

Results

The thematic analysis identified six major themes from hundreds of codes related to the overarching theme of how neuropsychological assessments were used in two youth forensics settings. Each theme and its characteristics are outlined in Table 1, and the connections between these themes and the overarching theme are presented in Figure 1.

Theme 1: Increased Understanding of Cognitive Strengths and Weaknesses by Youth, Family, Courts and Staff

The most prevalent theme concerned the increased understanding of cognitive strengths and weaknesses by youth, family, courts and staff. Continued patterns were identified from interviews with individuals from different professional backgrounds, including medical staff, educators, Corrections staff and case managers, which highlighted the impact of increased understanding. For example, it was noted that in the residential facility:

'The report has been fantastic because the way the report has written, you can understand it and you can relay that back to the care team and put it into language they can understand about the difficulty the young person has such as comprehension’ with ‘a more detailed understanding and what would best work’.

Importantly, the neuropsychological assessments increased understanding of how behaviours were related to cognitive strengths and weaknesses, and increased understanding of the young person beyond their criminal behaviour.

‘Yes they have criminal behaviour but please keep looking behind that criminal behaviour to see there may be valid reasons that this behaviour has been exhibited’.

‘[The neuropsychological assessments were] life-changing from my perspective in being able to speak to the fact that there are cognitive issues and not all behaviour is volitional and antisocial in itself’.

Participants noted the impacts of increased understanding for those working with the youth and also the youth themselves in terms of increased ‘knowing their own patterns of strengths and weaknesses’ and ‘relief of having people understand more’. The impacts of increased understanding were outlined by one participant, who noted that these became apparent after the neuropsychological services had ceased.

‘We aren’t getting a comprehensive background to be able to facilitate learning so we are flying almost blind in class now. Whereas [when] we can use the recommendations, we know what to do when we see something, but we are missing something more specific and what we can do for that individual, we are missing that ability. I think as well for the boys, some of them would bring their reports to class and say, “I need you to do this, this and this, because this is what my report says”. There was just this ownership and maybe just not labelling, but giving them a good understanding of why they can’t function in that way and have some weaknesses. Having it as part of the youth unit it’s part of the process; it’s normalised that they all have strengths and they all have weaknesses…It normalised that “hey I need help in this area”’.

The reports increased understanding of the rangatahi (youth) and also provided a more balanced perspective to recognise both their strengths and weaknesses.

Theme 2: Diagnostic Clarification

Participants noted that the neuropsychological assessment reports provided diagnostic clarification. For example, the interview data revealed ongoing instances of the assessments providing clarification.

‘…because it was diagnosed in the report and said he presents with this, this and this, we weren’t guessing anymore’.

Diagnosis through neuropsychological assessment was reported to provide increased understanding and clarity, as well as increased opportunities for referrals. Some participants noted ongoing concerns around the reliability and origins of previous diagnoses, with neuropsychological assessments providing clarification and up to date diagnoses regarding developmental or mental health problems.

‘…so we have a lot of kids come…there are a lot of suspicions and theories for what may be going on with our young people, and sometimes you are not sure what the diagnoses are. If they actually happened…whispered from being “we think this”…or “do they have this?” We can’t see if they have had this diagnosis or if they have (an) ID (intellectual disability) diagnosis, without this understanding [the report] is a really good roundup of these things in terms of challenges they are facing and the biggest thing that I have found helpful is the diagnosis of the IDs, because that gives them access [to services]; that’s it, it opens up doorways. A lot of the time you assume they are low functioning but to actually have it on paper that this is what they have scored at and it is official’.

Theme 3: Strengths-Based Approach/Adapt and Change Approach

The third theme focused on strengths and changes based on areas of difficulties. Increased understanding led to changes also based on recommendations contained in the report.

‘…little gems on how the care team can work more specifically with that rangatahi (youth)’.

The analysis also revealed that such adaptation was enhanced when the youth had understanding of both the change in approach and reasoning behind the change.

‘…given the feedback to them, it has been said out loud in front of them. "That it is obvious that you struggle with this so then it can be addressed when they are up jumping out the window and trying to do something. You can say “Remember, not your strong point but if you come back here we can give it five minutes”. It can reinforce that we know you struggle with this so this is how we are going to deal with it’.

The below extracts of individual cases outline adaptations made following neuropsychological assessments.

‘We were really focused on well-being and functioning. The social worker was a bit reluctant to say… we need to work on his offending behaviour. But actually (we stated)…he is really low functioning (that) is contributing to his offending behaviour so there needs to be support services around that…. I said you need to read through (the report) … they were getting confused as they thought it was mental health. So then we had to say no it wasn’t his mental health, it is his disability, ID…we have the disability here, so it was really good to communicate that’.

‘…he had (poor) concentration…very high with his photo memory and his visual (skills)…you may struggle to listen in situations, but we do know that you are good with that skill…he was wanting to be a tattoo artist…So that aligns with that. We were able to refer further on and advocate at family group conferences, he has skills to be in this area. It is not some random dream that doesn’t align with his skills with what he could be capable of’.

‘One example a young man that was dismissed for being thick at school, who was actually really good with numbers so we used numbers to talk about his health’.

‘Recently a young man who was much better with visuospatial skills and found it hard to process too much information. Thought it could be the case but it was good to have it in writing so we could tell how to work with him. Pass it onto the care team with their little sticky up thing. We knew getting him into the agriculture program, that was the kind of work he needed to do’.

‘An example would be one young man, I went over to the unit to tell him some side effects of some medication and he comes across as quite capable with a good level of understanding but your report told us that he’s quite good at putting on a front of understanding, so I went out and read the information to him and explained harder words. Then I answered any questions he had. Whereas if I had not realised his lower level of understanding and processing I may have just handed him the sheet and said here read this’.

The above extracts outline changes in approaches based on both strengths and areas of difficulty. Access to the reports meant that those working with the youth had increased understanding of their abilities as opposed to overestimating or underestimating each person. This led to a tailored approach at the level of the youth’s cognitive abilities, with particular focus on areas of strength. Effectively, a strengths-based approach can improve the youth’s confidence and ongoing capacity to improve through education and rehabilitation, as well as increase their long-term engagement with the rehabilitation processes.

Theme 4: Increased Access to Services, Referrals and Provision of Appropriate Services

The fourth key theme to evolve from the analysis captured how neuropsychological assessments led to increased access to services, referrals and provision of appropriate services. Participants detailed many instances of increased opportunities for the youth to be eligible for services, which would have otherwise not been available.

‘In terms of residential options and service provision in their place of origin it has been incredibly helpful and sometimes life changing’. 'Most of our young people fall through the cracks. They don’t meet criteria for mental health services; we don’t have a clear pathway for assessment for disability services. So without this service, there is a lot of people who are eligible but they are never going to be identified as such’.

This theme was exemplified by a particular case described by an interviewee regarding a young man.

‘…when he was diagnosed with the ID and so basically what happened was that he was given the diagnosis and it was official. Then he was able to be referred, he was initially referred to a disability organisation, he had access to 4 hours per week…he has been upgraded to 4 hours per day in the community if he needs it…which opens up placement options as well for disability supports for work’.

The assessments provided an opportunity for further services and then led to increase in service provision as his needs continued to be explored.

Theme 5: Impact of Engagement with the Legal System

Throughout the thematic analysis, the theme of impact of engagement with the legal system was detected. Participants frequently referred to the use of the report by judges, lawyers and within the court system. The neuropsychological reports increased understanding of how cognitive deficits and neurodiversity impacted offending behaviour, leading to changed outcomes for the young men in the legal system. The overall impact of neuropsychological assessment in the court process was exemplified by comments of one participant.

‘…crucial when judges get the assessment [report]…it has been useful to pass onto the lawyer and onto the court…out of that has come question of fitness to plea…for the court and the jurisdiction process to understand the young person…[to] change things for the [young person]’.

It also facilitated increased understanding of the court process for the young person with a ‘court appointed’ individual following report completion to assist the young person to understand the court process.

‘…sometimes…don’t know how to explain court to them’.

Participants provided examples of individuals who were directly impacted by the neuropsychological reports, with the following outlining a typical case.

‘A young person who came…was sitting in district court and on charges, homeless, was living in his car, alcohol was an issue. [The neuropsychologist] did the assessment and he came out with ID. We were going through the court process at the time, and we flung (sent) the report out to the people who needed to know and that changed the periphery of the of the court system for him. So he got the services he needed, the social worker…psychologist…It was like wow…people are actually reading [the report] and understanding this boy’.

Importantly, when discussing neuropsychological reports in the court system, participants invoked the positive impacts of reducing perceived recidivism, thereby reducing the burden of youth presenting to the courts. Participants attributed increased understanding of needs and diagnoses to reduce re-offending by youth.

‘It’s the kids that fall through the cracks. We don’t know what is wrong with them or why. We can’t get them referred, they don’t meet a criteria, and then we don’t understand how they are learning or emotional regulation or anything like that, and then they end up re-offending. I think it reduces reoffending’.

Interestingly, the link between increased understanding through neuropsychological assessment and perceived reduced offending was encapsulated by one participant as follows.

'I think you are running the risk of neurodevelopmental disability being ignored as part of the picture and criminalising disability in the justice sector…It is seen frequently in this setting…the assessment has provided a gateway to providing appropriate service provision to the youth that would otherwise never run across that. Otherwise, they would head onto a trajectory towards jail’.

The increase in appropriate services and understanding changes the trajectory of young men from alternatives of continued offending and incarceration.

Theme 6: Multi-Level Engagement with the Report to Benefit the Youth

The final theme described how reports were forwarded onto other services who worked with the young person external to the forensic unit. This multi-level engagement was believed to offer benefits for the youth. One participant described the impact in the community as follows.

'…highlighting things for social workers who they (the youth) will continue their journey with in the community’, to 'send out to others (outside of the residential facility) to assist in their work with them" such as being "used on discharge.. pass onto field workers, a few judges, assist in sentencing…GP reads them’ and ‘share with courts, colleagues and family’.

Discussion

The thematic analysis of interview data explored the use and benefits of neuropsychological assessments. The analysis revealed six key themes related to the utility of neuropsychological assessments in youth justice. These themes reflected: increased understanding of cognitive strengths and weaknesses; diagnostic clarification; increased access to services, referrals and provision of appropriate services; impact of engagement with legal systems; change and adaptation of approach with a strengths-based approach; and reports being forwarded onto other services who worked with the young person external to the forensic unit.

As outlined in Figure 1, neuropsychological assessments had a direct flow on effect on outcomes for the young men at multiple levels in the legal system, forensic residential facilities, community settings and healthcare settings, as well as for the youth and their family. The neuropsychological assessments provided more understanding of the background of the youth their cognitive abilities, and also led to diagnostic clarification. Such factors enabled changes in approaches by those working with the young men, referrals to appropriate services and improved outcomes in the legal system.

The thematic analysis demonstrated that neuropsychological assessment increased understanding of the youth and provided diagnostic clarification. This was consistent with previous findings (Sieg et al., 2019; Watt & Crowe, 2018) whereby neuropsychological assessment provided an important complete picture about the nature and severity of cognitive impairment and characterised the functioning of an individual (Watt & Crowe, 2018). The reports also increased the youths’ understanding of themselves. Normalising differences and strengths destigmatised areas of difficulty, which increased the engagement of the youth in their own rehabilitation and education. This was consistent with Rosado and colleagues (2018), who found that those who were provided with feedback following neuropsychological assessment reported improved quality of life, increased understanding of their condition and increased ability to cope at follow-up compared with those who had not received neuropsychological feedback.

From the perspective of those working with youth, increased understanding of the cognitive and psychological factors underpinning behaviour led to adapting approaches to focus on strengths and use of compensatory strategies for areas of difficulty. Consistent with these findings, Arffa (2008) found that neuropsychological assessment led to increased understanding of diagnoses and treatment planning in children. The interaction of increased engagement of the youth in their own rehabilitation and adapted interventions by those working with the youth may lead to flow-on effects, creating a cycle of ongoing improvements and longer lasting engagement with rehabilitation.

As hypothesised, increased understanding and diagnostic clarification from the neuropsychological reports led to increases in appropriate referral pathways, funding opportunities and referrals made to services. Participants provided multiple accounts of these instances. This was consistent with the review by Watt and Crowe (2018), who found inclusion of neuropsychological assessment reduced misdiagnoses and more reliably ensured individuals received the correct treatment. In the youth justice setting, this includes accommodation, placements and more suitable intervention/rehabilitation programmes. Sieg at al. (2019) highlighted differing use of healthcare and needs based on neuropsychological assessment. This suggested neuropsychological assessment was important to identify individuals at risk for greater use of services and may suggest the need to develop appropriate interventions for such individuals.

Neuropsychological assessments assist in gaining an understanding of functional capacity and the need for ongoing services such as accommodation, community integration, education placements, employment, financial assistance and development of skills in day-to-day living (Bennett, 2001; Hanks et al., 2008; Miller & Donders, 2003; Pastorek et al., 2004; Pritchard et al., 2012; Watt & Crowe, 2018). The prison environment represents a structured and routine-based setting to the extent that some studies reported a decline in cognitive functioning associated with imprisonment (Rowlands et al., 2020). Therefore, without completion of an in-depth neuropsychological assessment, the impact of cognitive impairment and need for appropriate services may not become apparent until the individual is released into the unstructured and chaotic community environment. Without suitable services, those with cognitive difficulties may be more likely to return to previous maladaptive behaviours that can lead to criminal activity, thereby perpetuating a cycle of recidivism.

In the same way that neuropsychological assessment better informs the provision of needed services and interventions, it also impacts court outcomes. The initial scope of the project focused on providing in-depth understanding of the youth to increase referrals to services in the community. The impacts in the court system were not initially considered by the researchers as the reports were not written for that purpose. As the service continued and reports were provided to others with the youths’ consent, a flow-on effect to the courts was observed. The trajectory of outcomes for youth in the courts changed. As Bush (2005) suggested, neuropsychological assessment in the forensic context can contribute to the understanding of human behaviour, whether transgressive or not, within the scope of biological, psychological and cultural factors. This provides the courts with a better understanding of the individual’s needs and appropriate services and increases the capacity of youth to engage in rehabilitation, thereby reducing the potential for re-offending.

Limitations

As an audit following the completion of the neuropsychological service, there were many individuals who were not contacted to explore the benefits of the reports. Further research would benefit from interviewing the youth and contacting their parents and caregivers to provide another perspective on report utility. Similarly, it would be useful to obtain feedback from those in the legal system and community to further understand report use.

Another area that would be beneficial to explore is the cultural fit of neuropsychological assessment, particularly as Māori comprise a large percentage of the youth justice population. Although this was not identified as a theme, further exploration is recommended. Dudley and colleagues (2014) suggested that although Māori participants identified many positive aspects of the neuropsychological assessment process, there can be disappointment that cultural identity remains invisible. This can have implications for cultural responsiveness leading to more accurate diagnoses, and more relevant and appropriate rehabilitation programmes.

Conclusion

The use of neuropsychological assessment can impact the trajectory of youth in the justice sector. Neuropsychological assessment provides an in-depth knowledge of the individual that leads to increased understanding and diagnostic clarification. This can lead to changed outcomes in the court setting, provision of appropriate services and adaptation of approaches by those working with youth. Further implementation of neuropsychological assessments as a standard assessment tool for youth has potential to improve the rehabilitation model of those in forensic settings and reduce recidivism.