Introduction - Troubled Waters and a Guiding Star

Polynesians navigated vast open oceans to Aotearoa, followed centuries later by Europeans, thanks to models of star positions that were scientifically accurate enough to enable replication and generalisation of successful exploration (Walker, 2012). Models with predictions that are replicable and generalisable are a universal taonga or treasure of all peoples, by which our species achieves wonders. A scientist/scholar practitioner model is central to the profession of psychology and problems occur if we neglect such principles. There has been the problem of insufficient replication in psychology (Open Science Collaboration, 2015). There has also been an over-reliance on “WEIRD” (Western, educated, industrialised, rich, democratic) population samples, rather than wider cross-cultural samples, which limits the generalisability of our knowledge (Henrich et al., 2010; Waitoki et al., 2024). There has been a proliferation of models, theories and complexity sometimes due to duplication (e.g., multiple terms for the same phenomenon), rather than depth of knowledge. Academic institutions by their nature incentivise knowledge specialisation, but this increases fragmentation over needed efforts at integration (Henriques, 2003; Mayer & Allen, 2013).

There is widespread dissatisfaction with dominant categorical diagnostic systems of mental health, such as the DSM-5/ICD-11. Criticisms have included the high rates of comorbidity, overlapping diagnostic sets, and people with the same “disorder” having only a single symptom in common and many non-shared symptoms. In brief, the reified diagnoses do not fit the data and are a poor basis for identifying risk factors and treatment needs (Cuthbert, 2014; Kotov et al., 2021). A crosscutting approach detailed within the DSM-5 to assess symptoms “cutting across” and shared between “disorders” is a concession acknowledging these difficulties, but the categorial diagnostic system remains dominant. DSM/ICD diagnoses have also been criticised for decontextualised pathologising of individuals, rather than recognising many phenotypic variations as predictable adaptations to social, environmental, ideological and economic threats (Johnstone et al., 2018; Te Pou, 2024). They have been criticised for poorly serving non-Western populations (Waitoki et al., 2024), which may be a facet of the larger problem that they serve everyone poorly (Johnstone & Kopua, 2019). The DSM is tailored for the US health system, which spends more than other wealthy countries, yet is an outlier in obtaining the worst overall outcomes (Blumenthal et al., 2024).

In response to these issues, new standards for research protocols, broader cultural research, and alternative frameworks for understanding psychological distress have emerged. Leading international proposals include the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (Cuthbert, 2014), the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) by an international collaboration of researchers (Kotov et al., 2021), and the Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF) by the British Psychological Association (Johnstone et al., 2018). There is ongoing debate regarding benefits and limitations of these compared with the DSM/ICD and other psychological approaches.

This article advocates for consilience or the unity of knowledge (Wilson, 1998) over choosing between competing models. Consilience suggests a deep, unifying structure to reality, where robust theories are supported by converging evidence from independent fields. The structure of psychological knowledge is analysed here by seeking converging patterns across major subfields, including psycholexical personality (looking for factor structure in the words used in different languages to describe people), cross-cultural (looking for commonality in what is valued by different cultures), psychopathological (analysing the structure in sets of mental health symptoms), biological (understanding the functioning of human psychological systems biologically and evolutionarily), and functional perspectives (how factors relate to surviving and thriving).

Arising from this approach, six core psychophenotype[1] domains are described that interact with each other and the ecological context to shape wellbeing. Table 1 links these psychophenotype domains to psychological research perspectives discussed in this article. These domains are recommended as an organising heuristic to assist psychological understanding and clinical formulation.

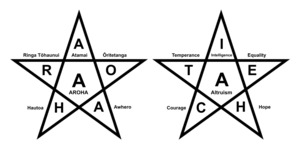

Although the specific names of these six domains are less important than the underlying science, clear labels aid in distinguishing and remembering them. However, it would be misleading to adopt terminology exclusive to one psychological subfield for domains that aim to integrate multiple perspectives. Therefore, for Aotearoa New Zealand, two mnemonics - AROHA and ITEACH (in Māori/English) were selected for this article. In AROHA, each letter represents a domain, with “AROHA” itself as the central domain. For ITEACH each letter signifies a domain. These mnemonics reflect the psychologist’s role of aroha (caring) and teaching and the focus of that care and teaching. The capitalisation of domain names emphasises their status as scientific constructs, which may differ from the varying colloquial interpretations. However, these descriptors may also be ignored or re-tailored to enhance accessibility.

Figure 1 illustrates a guiding star of cross-culturally valued domain development. This symbol was selected as a culturally common guiding motif, as were domain positions. The heart of the star is a system for care and attachment which is of central importance to the development of all other domains. The head of the star is a system for cognitive mapping, reasoning and perception. One arm of the star is for self-control and task achievement, and another arm is for social exchange and co-operation. The legs of the star are emotional systems because emotion is energy for motion away from threats and towards rewards. Brief lay descriptions of the six psychophenotype domains are as follows:

-

Atamai/Intelligence - cognitive mapping, reasoning, skills for perceiving

-

Ringa Tōhaunui/Temperance - behaviour control, self-regulation, skills for achieving

-

Ōritetanga/Equality – fairness, reciprocity, social skills for sharing

-

AROHA/Altruism – kindness, attachment, social skills for caring

-

Hautoa/Courage - threat avoidance emotions, skills for defending

-

Awhero/Hope - reward approach emotions, skills for transcending

Psycholexical Personality Traits

Psycholexical research posits that because languages evolved, they contain words for patterns in the world vital to human function and wellbeing. Therefore, analysing patterns in human languages helps reveal what is important to humans about humans. From such research the psycholexical five-factor model (FFM) of personality became widely known and influential in psychology (McCrae & John, 1992), and was referenced in proposals for linking normative function and psychopathology in DSM-5/ICD-11 revisions. Current psycholexical instruments assess personality by self or other report within putatively normal or “neutral” ranges. Psychopathology and aspects such as actual rather than perceived intellectual function are assessed separately.

The HEXACO psycholexical model of personality is an empirical and theoretical improvement over the FFM (Ashton et al., 2014; Ashton & Lee, 2007, 2020). The name HEXACO is derived from the factor names: honesty-Humility, Emotionality, eXtraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Openness. Its origins lie in cross-cultural research that repeatedly found six rather than five factors in non-US languages, and when a US language sample was weighted by frequency-of-use algorithms. These findings imply the FFM is likely an artefact resulting from a slightly skewed initial language sample lacking in ecological and cross-cultural validity. HEXACO’s key addition is a sixth factor, Honesty-Humility, which captures traits such as “sincerity” and “integrity”, distinct from Agreeableness traits (e.g., “gentle” and “kind”).

The IPIP-6, a slight variant of the FFM/HEXACO, has been normed on a New Zealand population sample of 5,981 participants (Sibley & Pirie, 2013). Key findings showed effects of age, gender, and economic deprivation on some factors. Honesty-Humility increased with age, Neuroticism decreased, Extraversion slightly decreased, and Conscientiousness rose from ages 20 to 50 years. Women scored slightly higher than men on all traits except Openness, and economic deprivation correlated with higher Neuroticism. After controlling for these factors, demographic differences among other factors such as ethnicity (Pākehā, Māori, Pacific, Asian) were minimal. Table 1 aligns FFM/HEXACO/IPIP-6 factors with AROHA/ITEACH domains.

Psycholexical personality traits are linked to health outcomes (Pletzer et al., 2024; Soto, 2019). A meta-analysis of over 200 studies showed that personality traits, particularly neuroticism, can be altered through intervention, averaging a half standard deviation change in 6 weeks (Roberts et al., 2017). These traits are genetically based and reflected in neurobiological structures (Adelstein et al., 2011). Personality factors represent families of related abilities that address ecological challenges (de Vries et al., 2016; Zettler et al., 2020). There is heterogeneity in the range of adaptive personality traits within and between people because there is heterogeneity in the range of ecological challenges to which they must adapt (Penke et al., 2007).

It has been argued that for clinical classification systems to be scientifically sound, they should start with normative, culturally-universal patterns of normal personality function (Leising et al., 2009; Nesse & Stein, 2012); that is, psycholexical personality traits. Most psychopathology relates systematically to personality traits and in many instances more than so-called DSM “personality disorders”. This leads to the conclusion that either all disorders are personality disorders or none are (Lengel et al., 2016; Zavlis & Fonagy, 2024). It has been argued that “models of personality variation could play a central role in shifting the entire DSM toward a more empirically based (and etiologically based) nosology” (Krueger et al., 2011, p. 325), and that “personality offers a better general framework for case conceptualization and intervention than the current psychiatric nosology” (Watson et al., 2016, p. 309).

Consilient with this approach, it may be observed from a cognitive behavioural therapy perspective that the personality-aligned AROHA/ITEACH domains broadly resemble cognitive, behavioural, social (fairness and kindness), and emotional (threat and reward) divisions in clinical case formulation. However, for clinical purposes, these domains require analysis and development from other major fields of psychology beyond the limitations of psycholexical personality research. The first field to be considered is cross-cultural psychology.

Cross-Cultural Psychology

Culture is the system of symbols and values, often encoded with language and stories, that helps guide human thought and behaviour, including the evolution of culture itself (Kitayama & Salvador, 2024; Lehman et al., 2004; Markus & Kitayama, 2010). There are a range of methods for studying patterns of psychological universals (Norenzayan & Heine, 2005). Evidence from many literature reviews suggests humankind has culturally encouraged development of a few fundamental phenotypic capacities or valued character strengths over our history (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Six core values seem to be shared across world ethical codes, philosophies, and religions. These have been labelled wisdom, temperance, justice, humanity, courage and transcendence in the positive psychology literature. They apply across the literature traditions of Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Hellenistic philosophy, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, and also seem integral to oral traditions, from the Masai of the African savannah to the Inughuit of Arctic environs (Dahlsgaard et al., 2005).

Universalism challenges both the exclusive ownership of these values by any single tradition and the claim that other unique cultural values are essential for success, -given prospering of peoples without such unique cultural values. We are all Africans, descended from the same anatomically modern human ancestors originating in East Africa approximately 250,000 years ago and sharing this common humanity (Vidal et al., 2022). Even “ancient” cultural innovations like writing—invented just 5,000 years ago—represent only 2% of our species’ timeline (Houston, 2004). Our shared human journey connects us all far more deeply than our relatively recent cultural divergences.

The original classification of these values by researchers intentionally avoided a premature technical taxonomy. However, recent studies indicated substantial predictive and conceptual overlap between character strength measures and psycholexical personality models (Fowers et al., 2023; McGrath et al., 2020; Stahlmann et al., 2024). An alignment based on these findings and their conceptual and theoretical basis as discussed in this article is shown in Table 1. By this account, these universal character strengths reflect culturally valued or “positive” phenotypic development and actions of these personality domains (Mayer et al., 2011), and there are clear evolutionary reasons why this would be so (Buss, 2008; Nesse, 2009a; Tooby & Cosmides, 1992). Although personality trait research began from a neutral descriptive position, personality traits are inherently evaluative and related to moral concerns (Buss, 1991; Kristjánsson, 2012; G. F. Miller, 2007). Another observation is that by reversing the implicit “should not have” lists of many DSM/ICD diagnostic criteria, a list of “shoulds” emerges that matches cross-culturally valued phenotypic development (Leising et al., 2009).

There has been insufficient analysis of Māori tikanga or cultural values from the exact research perspectives described above, but Table 2 shows examples of pre-European Māori whakataukī (proverbs/sayings) selected from many that encourage development of these cross-culturally valued phenotypes (Brougham & Reed, 1963; Hirini & Grove, 2023). This illustrates that Māori recognised the importance of these values prior to later colonial contact. These metaphorical expressions are adapted to the unique ecological niche of hunter gathering and agriculture in pre-European Aotearoa New Zealand. Wider cultural value systems include valuing not just of these phenotypes and their subdivisions, but valuing of their necessary supports and connections. This includes factors such as land, history, art, physical health, social ties, biophilia (affinity for nature), and adaptability as can be seen in Te Ao Māori systems (McLachlan et al., 2017; S. Pitama et al., 2007; Valentine et al., 2017). Collectively, these systems can be called cultures or worldviews although beyond cross-culturally valued phenotypes diversity of views and adherence to factors within such systems varies enormously (Houkama & Sibley, 2015; Rahmani et al., 2024).

The ecological context and individual factors shape opportunities and challenges for development of these phenotype domains. In contrast to positively valued phenotypic development, more negatively viewed forms are often termed psychopathology if of sufficient severity, and research approaches to these are reviewed next.

Research Domain Criteria (RDoC)

This and the following two sections review recent major initiatives challenging how psychopathology is conceptualised, and how this relates to perspectives already discussed. The RDoC initiative was developed by the US National Institute of Mental Health in response to concerns that the DSM/ICD was hindering scientific progress. It aims to guide research on the neurobiology of normal function and psychopathology (Cuthbert, 2014). Drawing on neuroscience, genetics and more, the RDoC framework outlines transdiagnostic domains, each divided into constructs (e.g., working memory, reward responsiveness) that represent core psychological processes. Constructs are further divided into units of analysis such as genes, cells, and neural circuits to reflect the complexity of mental disorders. The RDoC constructs have been linked to both personality factors and the HiTOP (Latzman et al., 2021; Michelini et al., 2021), as shown in Table 1. Not listed are the arousal domain (although this is linked to valence systems), and the sensorimotor domain (which is linked to perceptual and behavioural systems).

The RDoC was initially criticised for overly simplistic views of mental difficulties as “brain disorders”. However, recent revision acknowledges the importance of recognising that human traits develop within ecological contexts (Morris et al., 2022), although details about the implications of this remain limited in the RDoC system. Nonetheless, the RDoC allows investigation of the biological underpinnings of mental difficulties via detailed focus on mechanisms that cut across otherwise invalid DSM/ICD symptom clusters. The hope is that this will assist more precision intervention in the future, particularly for more biologically mediated difficulties such as neurodevelopmental dysfunction not explainable by environmental influence. RDoC is not presently intended as a formalised taxonomy but the HiTOP approach—reviewed next—attempts this task.

The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP)

The HiTOP is an alternative system for classifying mental disorders that was introduced to address limitations of the DSM/ICD (Kotov et al., 2021). Development by a large international consortium of researchers has relied on statistical and empirical methods to more accurately identify the structure and organisation of DSM/ICD symptom patterns by focusing on dimensions and patterns of co-occurrence.

The HiTOP factor structure that emerged from these efforts is organised into several broad overarching spectra including “Thought Disorder”, “Externalising Disinhibited”, “Externalising Antisocial”, “Detachment”, and “Internalising”. As shown in Table 1, these spectra largely map empirically and conceptually onto psycholexical models of personality and also relate to RDoC constructs (Kotov et al., 2021; Michelini et al., 2021; Widiger et al., 2019).

Placement of some mental health difficulties in relation to these HiTOP spectra is less clear, and they may occupy interstitial (between domains) or other positions. Such cases include somatic problems, although these have clear links to the Internalising spectrum (Widiger et al., 2019). The Detachment spectrum relates to low Extraversion and also to low Agreeableness, which reflects how the positive affect system motivates pursuit and maintenance of social relationships (Zimmermann et al., 2022). Mania is, by definition, an extreme positive valence state; its interaction with other systems is associated with the effects of Thought Disorder and Disinhibited Externalising behaviour spectra (Michelini et al., 2021). Features of dissociation similar to psychoticism, including reality distortion, support placement in the Thought Disorder spectrum (Kotov et al., 2020).

Systems are integrated and highly interactive rather than being isolated. For example, many problems are prominently associated with neuroticism/internalising systems, including somatic, sleep, sex, and eating troubles (Watson et al., 2022). However, their form is influenced by other phenotypic aspects—such as lower Conscientiousness with bulimia and higher Conscientiousness with anorexia, in the case of eating problems (Gilmartin et al., 2022). Traditional categorical diagnostic labels may reflect one prominent phenotypic characteristic (e.g., eating behaviour, or a particular social behaviour), with other phenotypic features being heterogeneously associated.

The HiTOP is not just another way of classifying DSM/ICD disorders. The clear finding of this and much other research is that DSM/ICD disorders do not exist as discrete entities. Instead, the phenotypic elements within such categories can occur alone or in enormously varying combinations. Although some patterns of covariance are more commonly occurring than others, for the purpose of clinical accuracy it is best to identify the specific phenotypic characteristics of a client as they present rather than placing them into an over-specified and scientifically invalid DSM/ICD category. The match to a single pole of some personality spectra also suggests potential deficits in DSM/HiTOP coverage and placement of phenomena. For example, in addition to the low Honesty-Humility characteristic of antisocial patterns, excessive Honesty-Humility (leading to humiliation, subservience, and victimisation in relationships) is an important clinical phenomenon.

A further limitation of the HiTOP is that although it offers greater accuracy in specifying phenotypic level occurrence of symptoms or traits, it does not focus on understanding the contextual development or adaptiveness of these symptoms or traits, or even whether they are best classed as symptoms or traits (DeYoung et al., 2022). There are many hidden epistemological assumptions behind terms referring to phenotypic variations, which poses a risk of perpetuating misunderstanding and inappropriate pathologising. This concern is examined by the PTMF, reviewed in the following section.

Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF)

The PTMF offers an alternative model for understanding mental distress, behaviour, and emotional suffering. It was introduced by the British Psychological Society’s Division of Clinical Psychology (Johnstone et al., 2018, 2019). The primary aim was to correct an imbalance of focus in traditional approaches such as the DSM/ICD. It is not a new or controversial proposal that we need to understand an organism in an ecological context over time. This encompasses interactions at increasingly larger levels of interaction such as family, community, culture, society, environment and biosphere, as well as increasingly reductive levels of analysis including physiology, circuits, cells, molecules, and genes (Morris et al., 2022; Tinbergen, 1963). Although the PTMF acknowledges reductive biological etiological factors in cases such as acquired brain injuries or neurological disorders, it emphasises that normative evolved defensive responses to threatening ecological contexts explain much other human distress.

The PTMF encompasses four core concepts represented by key questions:

-

Power: what has happened to you?

-

Threat: how did it affect you?

-

Meaning: what sense did you make of it?

-

Threat response: what did you do to survive?

Sources of power, threat, and meaning include biological, coercive, legal, economic, socio-cultural, interpersonal, and ideological factors, which shape individual responses. The PTMF advocates abandoning pathologising terminology for these responses, such as “symptoms” and “disorders”, where this obscures function and meaning. For example, what is labelled as “disorder”, might be more correctly termed “ordered by threat” in many instances. The PTMF urges strong questioning of epistemological assumptions in instances where DSM/ICD terms are still used. Many responses should be understood as probabilistically predictable responses to ecological contexts. Originally, seven “provisional patterns” of such responses were identified; for example, “Surviving disrupted attachments and adversities as a child” and “Surviving defeat, entrapment, disconnection and loss”.

The PTMF serves as a meta framework grounded in evolved human capabilities and threat responses, which are argued to apply universally across time and cultures. Recognising the imposition of DSM/ICD on Indigenous peoples such as Māori, it has been asked:

“Is the Western diagnostic paradigm simply another form of colonialism, perhaps more subtle than earlier versions, but equally damaging in its impacts?…”, and “Is it legitimate to offer the failed Western diagnostic model alongside indigenous ones, or does it need to be abandoned altogether?” (Johnstone & Kopua, 2019, p. 4).

Aligned with the PTMF and a consilient approach, the Meihana model (S. Pitama et al., 2007; S. G. Pitama et al., 2017) uses the metaphor of a waka or vessel navigating toward hauora (wellbeing). The model incorporates standard assessment areas including hinengaro (psychological), tinana (body/physical), whānau (social), taiao/whenua (environment), and wairua (meaning/connection), similar to the World Health Organisation and Te Whare Tapa Wha models of health (Durie, 1985). It also highlights additional contextual factors significant to many Māori----threats from ngā hau e whā (the four winds): colonisation (e.g., loss of economic resource base constraining development), racism (impacting ōritetanga/equity), migration (loss of people/place connections), and marginalisation (institutional barriers to participation)—and potential sources of positive power or ngā roma moana (ocean currents), which include āhua (identity and connections), tikanga (cultural values and practices), whānau (family and extended kin), and whenua (connections to land). Formulation using the Meihana model will benefit from adopting and being informed by a consilient approach to psychological knowledge, and formulation of the psychophenotype domains outlined in this paper may be informed by the Meihana or other culturally relevant models.

The PTMF emphasises the critical role of ecological context, functional responses, and universally evolved human capabilities in understanding and addressing psychological distress. It draws on a wide range of literature regarding phenotypic responses, but less so an analysis of deeper structural relationships. The models discussed in previous sections might provide significant empirical, theoretical and practical advantages in realising aims of this framework. To this end, a consilient model integrating the preceding perspectives with a broad range of literature from general and clinical psychology is presented in the following section.

Core Psychophenotype Domains

Cross-cultural analyses of human languages, value systems, biology, and psychopathology suggests six core psychophenotype domains are key to human wellbeing and function (see Table 1). These domains can be seen as families of closely related abilities and mechanisms converging on a fundamental human function related to ecological challenges. These phenotype domains are highly integrated and interactive, meaning that difficulties in one domain will likely affect or be influenced by other domains. They can be examined from different perspectives, from genes, to individual behaviour to their broader ecological and developmental context. Unfortunately, traditional diagnostic systems often overlook the significance of phylogenetic function and ecological context, which limits understanding of human behaviour and wellbeing.

There is adaptive variability in these phenotype domains, with different ranges adaptive to different ecological contexts. It is often helpful to understand a phenotype as being low or high on a dimension. For example, low levels of emotional threat reactivity (low neuroticism) may be helpful in some situations, but in other truly dangerous situations that same level may result in dangerous recklessness. Extreme phenotypic traits are more likely to be maladaptive in most ecological contexts, and more likely to attract labels associated with psychopathology in traditional diagnostic systems such as the DSM/ICD.

I will explore the main features of these six systems from a broadly ethological perspective (Tinbergen, 1963); that is:

-

What is the evolutionary development (phylogeny) of that phenotype system?

-

How does that system develop during an individual’s lifetime (ontogeny)?

-

What is the mechanism (e.g., hormones, behaviour)?

-

What is the system’s function, and what are common patterns of clinical difficulties and interventions?

It is important to preface the following by acknowledging the importance of luck, which has long been recognised as critical to individual differences in human suffering and flourishing (Meehl, 1978). We do not choose our genes or the environment we grow up in, yet these factors shape our thoughts and behaviour, and different versions of those factors would have led to radically different versions of self and “me” (Gilbert, 2006, 2009). If we work hard and achieve a goal, it is because of luck that we have a brain with ability and motivation necessary for this achievement, and similarly if the reverse is true. The more we understand the deep patterns of causation that shape us, the less room there is for free will (Sapolsky, 2023). Although potentially unsettling, such insights encourage greater humility about success and forgiveness for failure, and a fairer and kinder understanding of human experiences.

Atamai - Intelligence and Perceiving - The Cognitive Mapping System

Psychological problems… may result from commonplace processes such as faulty learning, making incorrect inferences on the basis of inadequate or incorrect information, and not distinguishing adequately between imagination and reality. (Beck, 1976, p. 19)

The function of this phenotype domain is cognitive mapping, via exploration and processes involved in learning, such as reasoning and perception. All core human needs and abilities ultimately depend on the ability to process information and recognise and map patterns competently (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Johnstone et al., 2018). The personality trait of Openness/Intellect is associated with ideas, creativity, and curiosity, and is the trait most linked to intelligence, IQ, and cognitive ability (Bartels et al., 2012; DeYoung et al., 2012, 2014; Nusbaum & Silvia, 2011). Although intelligence is often seen as separate from personality, it may be viewed as a facet of Intellect (DeYoung, 2011). Intellect encompasses perceived intelligence and has more to do with how information is processed and organised, whereas Openness encompasses motivation and interest in aesthetics, novelty and complexity (DeYoung et al., 2005, 2014). Neurologically, this domain involves perception, language, and memory processes, with key links to attention, control and positive valence systems, which reflects that learning is guided by control processes and driven by reward systems (Abu Raya et al., 2023; DeYoung et al., 2005). When evaluating intelligence, it is important to consider what may be adaptive within an individual’s ecological niche, rather than applying inappropriate cultural or ecological standards.

The Openness/Intellect personality trait was also labelled “Culture” by some early researchers. In addition to innate cognitive heuristics, humans are highly cultural and transmit symbolic-linguistic information across generations. Cognitive maps create justification systems for behaviour (Henriques, 2003), and these often occur as stories that convey information in various forms, including factual statements, fables and myths (lies containing truths), and metaphors that translate understanding across cognitive domains. In oral cultures such as traditional Māori society, pūrākau or memorable stories play a crucial role in information transmission (Johnstone & Kopua, 2019; Ware et al., 2018). The fundamental structure of a story involves human will and some form of resistance to it, allowing for the inference of salient patterns (Dutton, 2009). Humans possess a sophisticated story system that enables self-representation, self-awareness and even narratives about these self-stories (Damasio, 2010; Higgins & Pittman, 2008).

The acceptance and rejection of storied information is a key process in human development (Fivush, 2011; Markus & Kitayama, 2010; McLean et al., 2007). Stories perceived as true activate reward systems and may be incorporated as part of justification systems, whereas those perceived as false elicit disgust and are rejected (Harris et al., 2008; Sacks & Hirsch, 2008). Brain metabolism is expensive, so there are also numerous trade-offs between speed and accuracy of processing (Oliver & Ostrofsky, 2007). Initial stories also influence the acceptance of later narratives, so it is important to establish early adaptive stories (Bloom & Weisberg, 2007). Trust in the cultural authority one is born into fosters complex behaviours, but also leaves individuals susceptible to maladaptive narratives. To a greater degree than any other primate, human children “over imitate” adults (Nielsen & Tomaselli, 2010), instinctively trusting in the utility of behaviours they cannot fathom in any immediate temporal context.

Activating the neural systems for self-observation and reflection on self-stories is a universal process in psychotherapy (J. Allen et al., 2008; Beitman & Soth, 2006). Problems with stories include clinging to overly rigid stories, being overwhelmed by un-storied experience or lacking a narrative strong enough to contain traumatic pain. Being unable to comprehend and fit threatening experience to a story that helps navigate the threat causes distress and cognitive preoccupation, driven by negative valence systems.

As discrepancies arise between cognitive mapping ability and ecological demands, individuals may seek help or be labelled as needing help. Difficulties in perception and cognition can stem from “low” operational levels due to lack of education, mentoring or valid information, or from conditions such as intellectual or learning disability or dementia (Abramovitch et al., 2021). Alternatively, difficulties may reflect excessively “high” activity, such as hypersaliency in apophenia, delusional beliefs, and psychotic experiences (Bell et al., 2006; Kapur, 2003; Rhodes & Jakes, 2004). Openness is positively associated with psychoticism whereas Intellect is negatively associated (Blain et al., 2020; DeYoung et al., 2012; Longenecker et al., 2020)

From a psychotherapy perspective, education and various cognitive techniques have been used to teach skills in this domain, as noted by the opening quote from Aaron Beck. More recently, other so called “third wave” therapies have broadened the approaches relevant to this and other phenotype domains (Hayes & Hofmann, 2017). For example, mindfulness approaches increase Openness and attentional components of the behaviour control system, and reduces activation of the threat system (Altgassen et al., 2024).

Ringa Tōhaunui - Temperance and Achieving - The Behaviour Control System

The function of this phenotype domain is behaviour control and the selection and organisation of actions to achieve goals. A core human need is achievement and competence, and the ability to exercise agency and control (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Johnstone et al., 2018). Conscientiousness, a key personality trait, is tied to self-regulation and executive functions such as attention and shifting mental sets (Fleming et al., 2016; Inzlicht et al., 2021; Krieger et al., 2020), and to important life outcomes including achievement and health (Bogg & Roberts, 2013; Duckworth et al., 2019).

Self-awareness involves recognising our existence in time as well as space, which enables us to learn from the past, plan for the future, and act in the present. We balance immediate desires versus the needs of our future selves, often temporally discounting future desires based on their distance in time (Boyer, 2008). This can lead to behaviours in the short term that the future self may regret, which highlights the challenges of self-regulation (Ainslie, 2001; Heatherton, 2011). Links to positive and negative valence systems both motivate and inhibit goal pursuits, with executive function and other behaviour control systems mediating between competing goals in a temporal perspective (Inzlicht et al., 2021). For example, positive emotion can prompt impulsive action but also long-term achievements through delayed gratification, depending on behaviour control mechanisms.

Life history theory is important to understanding development in this domain (Ellis & Del Giudice, 2019; Schiralli et al., 2019). It helps predict individual development and attitudes towards present versus future, including temporal discounting. Organisms make trade-offs such as prioritising current versus future reproduction or resource use based on ecological conditions. In general, the pattern is that harsh unstable ecologies lead to the development of phenotypes that favour immediate behavioural investment and reward (fast life history), whereas more stable ecologies favour phenotypes that can make the most of future focused behavioural investment and reward (slow life history). Fast life history traits include earlier biological maturation, quicker risk/reward assessments, short-term goal focus, and riskier social behaviours that may quickly garner resources. Although traditionally viewed as undesirable, a recent project aims to understand some of these traits in a less stigmatising way as skills developed in adversity or “hidden talents” (Ellis et al., 2023).

Mismatches of our phylogeny with modern ecology also contribute to problems in this domain. Our appetitive system evolved for a food-scarce hunter-gatherer ecology but now exists in a food-rich environment, which contributes to high rates of metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes (Abuissa et al., 2005; Gluckman et al., 2011). Addictive substances (e.g., high calorie foods, drugs) and behaviours (e.g., gambling, excessive consumerism) can hijack our neurological reward pathways, especially in an ecology where these behaviours are promoted by availability and advertising. This can lead to prioritisation of unhealthy short-term reward strategies over options more conducive to long-term well-being (Dittmar, 2007; Gilbert et al., 2009; Pani, 2000; Sellman, 2009).

Difficulties in this domain may be understood as existing on a dimension ranging from dis-constraint and impulsive behaviours, marked by a lack of control (e.g., attention deficits, impulsivity, substance use, bulimia), to over-constrained and compulsive behaviours, characterised by perseveration and over-control (e.g., perfectionistic behaviours, compulsions, anorexia; Bohane et al., 2017; Flett et al., 2022; Gilmartin et al., 2022; Gomez & Corr, 2014; Krueger et al., 2021; Mike et al., 2018; Robbins et al., 2012; Stoeber et al., 2009). Addictions may start impulsively but become compulsive.

In addition to cognitive techniques such as psychoeducation, training of self-regulation skills and alteration of ecological features or environmentally mediated stimulus contingencies are common strategies used to assist with problems in this phenotype domain (Diamond, 2013; Javaras et al., 2019; Reiss et al., 2014). For self-regulation difficulties due to traumatic brain injury, cognitive remediation involves training on self-regulation tasks to encourage neuroplasticity, with the hope that learning generalises to untrained tasks and everyday function. Techniques to improve planning and organisation and minimise distraction are used for attention-deficit problems, often adjunctive to medication. For substance abuse and general health related issues, motivational interviewing clarifies discrepancies in motivational states to support the saliency of choices aiding longer term wellbeing (W. R. Miller & Rollnick, 2023). Exposure and response prevention often helps with compulsive behaviours (Ferrando & Selai, 2021).

Ōritetanga - Equality and Sharing - The Fairness System

The function of this phenotype domain is fairness and reciprocity in social situations, and the ability to choose cooperative mutualistic relationships rather than those characterised by exploitation or submission. A sense of justice and fairness within the social domain is a core human need (Johnstone et al., 2018). The personality factor of Honesty-Humility relates to the capacity to maintain equity and reciprocity in social relationships, thereby avoiding exploitative interactions (Ashton & Lee, 2007; de Vries et al., 2016; Zettler et al., 2020). From early in life, people instinctively reject deception and unfair treatment (Geraci & Surian, 2011; M. M. Lucas et al., 2008; D. T. Miller, 2001). Research shows primates and humans will tolerate mild-moderate inequality for prosocial reasons but resist higher levels (Brosnan et al., 2010; Fehr & Rockenbach, 2004; Goette & Huffman, 2007). Prolonged exposure to inequality harms health and social cohesion (Jackson et al., 2006; Patel et al., 2018; van den Bos, 2020; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2017). The need for reciprocity does not negate the possibility of hierarchies that can have important functions, such as mentoring or leadership, provided there is still sufficient mutual benefit (Avolio et al., 2009; Bugental, 2000).

Cooperation between non-kin and even across species has evolved in many species, primarily through the equity maintaining processes of reciprocal altruism/cooperation (Axelrod & Hamilton, 1981; R. L. Trivers, 1971). Evolution of cooperation is favoured by mutualism where both parties benefit by achieving something neither could alone, either immediately or over an extended series of exchanges. Analysis of a variety of competing social strategies suggests a three-component strategy is most successful: (a) altruistic cooperation outcompetes purely selfish approaches; (b) maintenance of retribution/guarding is necessary to resist serious injury arising from non-reciprocators; and (c) forgiveness prevents mutually destructive feuds developing, and reopens the possibility for beneficial cooperation after ruptures.

A singular strategy of pure altruism is neither sustainable nor good if equality and reciprocity is ignored. If one does not react to significant injury caused by another, then that person is free to injure again, including against others. Justice is therefore a culturally universal value reflected in laws and ethics across time and place (Dahlsgaard et al., 2005). However, although guarding is necessary, justice that ends at revenge and punishment is not justice but simply revenge. Justice involves sanction but where possible also forgiveness with restoration to mutualism (Ho & Fung, 2011; McCullough, 2008; Nascimento et al., 2023).

Retribution/guarding strategies do not always have to involve direct confrontation, imprisonment, or other dramatic action. Indirect relational aggression such as gossip is often just as effective (Archer & Coyne, 2005) because reputation is crucial in social species. Most people are highly socially conscientious, as seen in the 10-1 rate of social phobia (fear of negative evaluation) compared with psychopathy (lack of social conscientiousness) (Nesse, 2009a). However, exploitative strategies such as psychopathy may pay off evolutionarily in ecological niches associated with a fast life history strategy, despite risks of retaliation (Brazil et al., 2021; Ene et al., 2022).

Cooperation activates reward centres in the brain (e.g., the ventral striatum), with oxytocin fostering trust and connection, whereas unreciprocated cooperation and perceived inequity activate the amygdala and insula, triggering anxiety, anger, and a desire for retaliation (Rilling & Sanfey, 2011). These impulses can be moderated by the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which enables perspective-taking and consideration of factors such as stress, kinship ties, friendship, and potential future interactions (O’Gorman et al., 2005).

Many difficulties in this domain can be understood as existing on a dimension of exploitation and coercion, with low consideration given to the rights of others at one end (e.g., psychopathy, narcissism, machiavellianism, deceitfulness, aggression) and excessive rights given to others at the high end (e.g., subservience, humiliation, surrender, passivity, victimisation; Feiring et al., 2010; Lee & Ashton, 2014; McDonald et al., 2012; Muris et al., 2022; Pereira et al., 2020; Schiralli et al., 2019). Exploitative and coercive relationships can occur in groups as small as two people, larger groups such as gangs, cults, or even large organisations or countries governed by authoritarian regimes. Some groups can struggle to receive equal recognition of their rights; for example, minority ethnic, sexual, disability, and cultural communities. Problematic cultural and economic systems, including environmental degradation impacting rights of current and future generations, require wider corrective societal responses.

People with serious deficits in respecting others’ rights will often be sanctioned by criminal justice systems, with intervention efforts then focused upon addressing specific risk factors and trying to develop capacity for living a “good life” where others’ rights are respected (Bonta & Andrews, 2023; Carter et al., 2021; Lutz et al., 2022; Ward & Brown, 2004). Those struggling to assert their own rights can benefit from building this capacity (Speed et al., 2018). Abusers and abused benefit from diverse interventions aimed at developing phenotypic capacities and ecological support, so core human needs can be achieved outside of highly exploitative relationships.

AROHA - Altruism and Caring - The Kindness System

The function of this phenotype domain is kindness and caring for others, a prerequisite of which is care for self; both abilities require recognition of and response to mental states. A core human need is social belonging and care, and secure attachment and loving early relationships are the fundamental basis for optimal development of all other phenotype domains (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Bowlby, 1982; Deci & Ryan, 2000; Hare, 2017; Johnstone et al., 2018). Adaptive care by parents and extended kin networks (alloparents) appropriately matches care to a child’s developing phenotypic systems, holding the child’s mind in mind and scaffolding ahead of their developmental needs (J. Allen et al., 2008; Grusec, 2011).

From a phylogenetic perspective, humans have been selected by evolution to perpetuate their genes, which can only occur via significant altruistic care from individuals towards kin. The goal of self-survival is secondary to the evolutionary goal of inclusive fitness, which deeply influences human nature and phenotypic development (see Box 1). Therefore AROHA/Altruism is the central most important phenotype domain (hence its position in Figure 1), supported by and integrated with the other five domains.

Desire for both kindness (altruism) and fairness (equality) in long term social partners and mates is a culturally-universal priority (Buss, 1989; Cottrell et al., 2007; G. F. Miller, 2007; Nesse, 2009a). Individuals suffer increased pain, health problems and mortality if they perceive they are not meaningfully and reciprocally affiliated; evolutionary novel conditions have eroded extended family structures and social supports in many societies, which increases such difficulties (Heinrich & Gullone, 2006; Holt-Lunstad, 2024; MacDonald & Leary, 2005).

The personality trait of Agreeableness is the domain of altruism and affection and associated with trait adjectives such as kind, warm, gentle, cooperative, and compassionate (De Raad et al., 2014; Sheese & Graziano, 2004). Agreeableness depends upon mental state decoding, empathy, theory of mind, and mentalising ability (T. A. Allen et al., 2017; Nettle & Liddle, 2008; Pisanu et al., 2024). Brain activation during theory-of-mind tasks predicts individual differences in Agreeableness and social cognitive ability (Udochi et al., 2022). The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex differentially processes social vs non-social information dependent on Agreeableness (Arbula et al., 2021). Hormones such as oxytocin are involved in decreasing activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (stress response), enhancing immune system function and generating feelings and behaviours of love and affiliation (Anestis, 2010; Uvnas-Moberg, 1998). Agreeableness is the personality trait most dependent upon environmental versus genetic influence in terms of development (Laursen et al., 2002), and is strongly linked to life outcomes and flourishing (Wilmot & Ones, 2022).

Difficulties in this domain can be understood as existing on a dimension of capacity and motivation for kindness and care towards self and others. At the low end there are difficulties in recognising and/or responding kindly to mental states of others (e.g., detachment, disagreeableness, criticalness), whereas at the high end are problems with hyper-empathising, dependency, gullibility, and indiscriminate kindness. These difficulties may result from attachment trauma and lack of sufficiently nurturing early relationships (J. Allen et al., 2008; Gore & Pincus, 2013; Luyten et al., 2024; Schaller, 2008; Tone & Tully, 2014), or other developmental aetiologies as occurs with autism or the genetic condition of William’s syndrome (Järvinen et al., 2013; Lodi-Smith et al., 2019; Riby & Hancock, 2008; Shalev et al., 2022). The category of borderline personality disorder is best avoided because it includes so many potential phenotypic variations that it “obscures rather than illuminates” (Mulder & Tyrer, 2023, p. 148), but its unstable interpersonal component and attachment/detachment switching relates to the function of this domain (Hepp et al., 2014).

If contact with others has often involved danger, the caring system will be conditioned with coactivation of the threat system. Therefore, attachment trauma can block the healing benefits of compassion from others and self (J. Allen et al., 2008; Gilbert, 2009). Overcoming this pattern is a key goal in therapy, and establishing a therapeutic alliance or helping create compassion towards self may be significant interventions. Therapists take on the role of alloparents (Young et al., 2003), providing a secure base for the client and enabling exploration of “schema” and different ways of being. Therapy is construed as providing developmental help of duration and intensity proportional to the degree of underdevelopment or mismatched development of core phenotype domains. Clients feel understood and valued, which generates a sense of security that in turn facilitates mental exploration (Ackerman & Hilsenroth, 2003).

Hautoa - Courage and Defending - The Threat System

The function of this phenotype domain is defence, and avoidance or overcoming of threats in one’s ecological niche. A core human need is safety from threats, which necessitates being able to experience and adaptively manage a range of threat relevant emotional responses (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Johnstone et al., 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Neuroticism is the personality trait of negative affect and emotional threat reactions. It is associated with many mental health issues and often motivates help seeking (Ormel et al., 2013; Watson et al., 2022; Widiger & Oltmanns, 2017). Lower levels of neuroticism are associated with improved life and health outcomes, up to the point where a paucity of threat reactivity becomes maladaptive. Therefore, as shown in Table 1, this trait is often reverse-scored as “reverse neuroticism” or “emotional stability” to align with other personality traits. Sadness and depression are related but also involve anhedonia and low positive affect, so are discussed in the following section addressing the reward system.

First responses to an imminent threat involve adrenergic sympathetic nervous system arousal, and flight (fear) or fight (anger) responses to avoid or overcome the threat. For more protracted threats, cortisol-driven allocation of metabolic energy towards threat analysis and monitoring and away from other systemic functions occurs. Ruminative problem analysis (worry) may generate further options for dealing with the threat or, if not, effort at resistance may be depressed. Therefore, threat responses can involve avoiding, attacking, analysing, or accepting threats, with shifts between responses as information and feedback from other phenotypic systems is processed (Monroe, 2008; Nesse, 2009b; Schneiderman et al., 2005; Taylor & Stanton, 2007). A certain level of challenge allows development of resilience in the threat system and post-traumatic growth, but as stress or “allostatic load” intensifies or persists, overload and health problems such as immune deficiencies, cognitive impairment, and somatic difficulties may occur.

The threat system’s reactivity develops in response to genetic and ecological conditions, with individuals in threatening ecologies developing heightened threat responses. Although these reactions can be detrimental to long-term health, they may also represent adaptive fast life history strategies that prevailed in human evolution (Ellis & Del Giudice, 2019; Flinn, 2006), and—consilient with a PTMF approach—defensive adaptations to anticipated threats. Additionally, a phylogenetic “smoke detector” principle operates, so that people are prone to false “panic” alarms as a byproduct of avoiding potentially deadly missed alarms (Baumeister et al., 2001; Gilbert, 2006; Nesse, 2001). Phylogenetic mismatches to the modern world likely include general overactivity and mismatched threat valuation. For example, fears develop easily to snakes as compared to evolutionary novel stimuli like cars, despite the latter posing a higher mortality risk in the modern world (Öhman & Mineka, 2001).

Problems in this phenotype domain can be understood as existing on a scale of emotional threat reactivity to diverse features of self (e.g., shame, self-criticism), others, and the world. At one extreme, even low-level threats trigger intense emotional responses of anger, anxiety, and stress; at the opposite end, severe threats fail to elicit response, leading to recklessness, risk taking, or apathy. Evolutionary pressures would have quickly eliminated individuals with extremely low emotional threat reactivity in the environment of evolutionary adaptation (EEA), making such cases rare. For example, a woman with bilateral amygdala lesions of Ubach-Wiethe disease exhibited fearlessness, reaching for poisonous snakes and spiders in an experiment and showing no fear during life-threatening crime and abuse in her life, despite having average IQ, language and memory abilities (Feinstein et al., 2011).

Difficulties related to the threat system were historically divided into a dizzying array of diagnoses in the DSM/ICD, complicating intervention testing and matching. Recent approaches identified commonalities among problems related to the threat system, both in aetiology and treatment generalisation. The “Unified Protocol” has been successfully implemented across the Americas, Asia, Europe and the Middle East. It prescribes general psychoeducation about threat emotions, adjustment of cognitive misappraisals, prevention of emotional avoidance, and alteration of unhelpful emotion driven behaviours via exposure and opposite action (Barlow et al., 2014; Cassiello-Robbins et al., 2020). Metacognitive therapy develops awareness and escape from cognitive attentional syndrome, where attention processes are excessively self and threat focused (Capobianco & Nordahl, 2023). Compassion-focused therapy recruits the altruism/kindness system to reduce shame and self-criticism and lower neuroticism (Gilbert, 2009; Pfattheicher et al., 2017).

A key assessment in this domain is understanding whether a person’s threat response strategies—attacking, avoiding, analysing, or accepting—are well-suited to their ecological circumstances. The answer guides potential interventions, as a maladaptive strategy in one context may be adaptive in another (Barlow et al., 2014).

Awhero - Hope and Transcending - The Reward System

The function of this phenotype domain is reward and approach of opportunity in one’s ecological niche. A core human need is that for growth, hope, meaning and purpose in life, and transcending “what is” for “what could be” (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Johnstone et al., 2018). Extraversion is the personality trait of positive affect, approach motivation, and reward, and is associated with activation of brain regions involved in such processes (Hermes et al., 2011; Lai et al., 2019; R. Lucas et al., 2000; Smillie et al., 2015), Higher levels of Extraversion correlate with wellbeing across the lifespan (Gale et al., 2013; Kokko et al., 2015). People who score highly on Extraversion are on average more energetic, outgoing, and sociable—although are also happier even when controlling for levels of sociality, reflecting that while the core feature of this domain is positive affect and activation, human incentives are frequently social in nature (Hampson, 2012; R. E. Lucas et al., 2008). This phenotype domain motivates cognitive and behavioural goal pursuit in addition to social engagement. Those who derive a higher proportion of positive affect and reward from ideas and tasks relative to sociality are described as more introverted, but can also achieve wellbeing via this pattern (Hills & Argyle, 2001).

Problems in this phenotype domain can be understood as existing on a dimension of positive affect, activity, and approach motivation. At the low end, positive affect, activation. and goal pursuit are depressed with experiences of melancholia, sadness, anhedonia, lassitude, and social detachment (Andrews et al., 2020; Andrews & Thomson, 2009; Watson et al., 2022; Watson & Naragon-Gainey, 2010). At the high end, elevated activation leads to euphoria, grandiosity, and mania, where goal pursuit can become excessive and metabolically unsustainable, such that exhaustion and change to a depressive state eventually occurs (Barnett et al., 2011; Kirkland et al., 2015; Michelini et al., 2021; Quilty et al., 2009; Stanton et al., 2017; Tackett et al., 2008). High activation can also lead to creativity, productivity, and social status, so context is key (Baas et al., 2016; Kirkland et al., 2015).

Although the adaptive function of fight/flight strategies are more commonly recognised, low mood is frequently over-pathologised, which ignores potential adaptive features (Andrews & Thomson, 2009; Horwitz & Wakefield, 2007). For example, individuals with mild-moderate depression often perform better in certain tasks because of reduced self-deception, a phenomenon known as depressive realism (Moore & Fresco, 2012). In particular, the threat-focused attention, lower self-deception, and lower social cooperativeness often characteristic of depression are likely to be helpful in avoiding exploitative social situations (Soderstrom et al., 2011; Surbey, 2010). Anhedonia-induced behavioural inaction allows metabolic energy to be devoted to a reworking of one’s “cognitive map” or internal working model of the world, self, and others (Welling, 2003), including grieving and desistance from unachievable goals (Wrosch & Miller, 2009).

This strategy of withdrawal from goal pursuit for persistent threat-focused analysis can be situationally mismatched, just as inappropriate fight/flight (e.g., panic attacks) or acceptance strategies (e.g., tolerating abuse) can be mismatched. However, cases of mismatch should not overshadow and pathologise the core adaptive features present in low mood (Andrews et al., 2011, 2020; Andrews & Thomson, 2009; Crespi, 2020). Consistent with a PTMF perspective, it is important to understand the normative nature of inner conflict (Oliver & Ostrofsky, 2007). From an intervention and prevention perspective, altering detrimental ecological features and developing a person’s problem solving/analysis mechanisms, such that relevant core human needs may be pursued more effectively, is informed by these facts.

Interventions for this domain also include clarifying values, goals, and activities so that these are aligned with someone’s phenotypic capacities, ecological circumstances and core human needs (Epton et al., 2017; Matheus Rahal & Caserta Gon, 2020; McEwan et al., 2016). Whai Tikanga value cards are a helpful tool for doing so in a Te Ao Māori cultural context (McLachlan et al., 2017). Linking back to evolutionary principles, therapy aims to enhance variation, clarify selection, and commit to adaptive behaviours (Hayes et al., 2020).

Conclusion - Ahau Whakaako (ITEACH)?

This article has explored unifying connections across psycholexical personality, cross-cultural, psychopathological, biological and functional perspectives, culminating in a consilient heuristic of six core psychophenotype domains. These domains may be characterised as ultimate, universal, and unavoidable: ultimate, in the ethological sense of having long phylogenies as evolved survival functions; universal, in that they are valued across all cultures; and unavoidable, in that their development is essential for both survival and flourishing. Key features of each domain, along with patterns of potential maladaptation and intervention, have been presented to help inform clinical formulation and practice. Three primary conclusions emerge from this synthesis:

-

An empirically- and theoretically-grounded six-factor model of personality, and associated psychophenotypic variation, provides a more robust and structurally-sound foundation for clinical psychology and psychiatry than alternatives.

-

The universally shared and essential function of cultural traditions is to support the development of personality, or psychophenotypic capacities, vital to surviving and thriving.

-

Most psychopathology is best understood as extremes of personality, or psychophenotypic variation, that is either developmentally mismatched to regular ecological conditions or defensive evolved responses to ecological threats.

This is certainly not the first article to advocate for such an approach. However, while many articles in the scholarly literature detail specific connections, this article aims to collate a helpful summating overview of the whole, and with reference to the Aotearoa/New Zealand culture and context.

The most immediate implication for clinical teaching and practice is further de-emphasis on over-specified DSM/ICD diagnoses, which leading professional bodies increasingly recognise as scientifically invalid and clinically limiting. Instead, specific psychophenotypic variations as they function in ecological context and relate to hauora/wellbeing should be described. Existing psychometrics can inform formulation of these psychophenotype domains and thresholds for service access. Psychologists’ practice of clinical formulation already matches this approach and is strengthened by the knowledge and structure described in this article.

An overview of this nature cannot explore all nuances and limitations, and research continues to emerge and refinement is expected. Nonetheless, it is hoped that the psychological perspectives discussed and consilient approach advocated contributes to reflection on how our knowledge may cohere, and to understanding and nurturing of what matters most.

A psychophenotype refers to the observable psychological characteristics or traits of an individual, particularly as they relate to cognition, behaviour, sociality and emotion, - that arise from the interaction of genes (genotype) and the environment.