Introduction

Internationally, mainstream psychology has been dominated by research primarily conducted in Anglo-American contexts (Arnett, 2008; Fish et al., 2023). As Arnett (2008) argued, psychological researchers publishing in leading psychology journals in the United States restricted their focus to less than 5% of the world’s population. In Aotearoa New Zealand, the discipline of psychology is not exempt from being influenced by monoculturalism and is typically taught from a Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic (WEIRD) perspective (Abbott & Durie, 1987; Groot et al., 2018; Levy & Waitoki, 2015). Scholars in Aotearoa have challenged the uncritical application of WEIRD psychology (Groot et al., 2018; Lawson Te-Aho, 1994; Pomare et al., 2021), and called attention to the ramifications of racism, colonisation and injustices on the well-being of minoritised communities (Pomare et al., 2021; Waitoki, 2019). The failure of the Crown to uphold Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles in the regulation, training and employment of the psychology workforce led to a claim lodged to the Waitangi tribunal (Levy, 2018).

Furthermore, there are ongoing concerns that the discipline falls short of considering the needs of minoritised groups, such as Pacific peoples (Ioane, 2017), Asian peoples (Liu, 2019), migrants and refugees (Liu, 2019) and rainbow and takatāpui (people who identify with diverse genders, sexualities and sex characteristics; Hayward & Treharne, 2022). The ethnocentrism of psychology has detrimental consequences for Māori, racialised and minoritised individuals to participate effectively in psychology. Ongoing reporting by the National Standing Committee on Bicultural Issues in collaboration with the New Zealand College of Clinical Psychologists and New Zealand Psychological Society shows that the history of monoculturalism in psychology led to Māori students internalising deficit-focused frameworks, experiencing rejection from cultural networks and having little access to their own culturally derived knowledge bases (NSCBI et al., 2018).

Over the years, concerns have been raised about the individualistic framing of psychology, leading to calls for psychology to be taught in a culturally informed and safe way (Groot et al., 2018; Ioane, 2017; Liu, 2019). For example, student representatives from the New Zealand College of Clinical Psychologists expressed regret that ‘there had not been more emphasis on cultural awareness not just of Māori/Pasifika, including more practical cultural safety (e.g. learning and practising karakia), but also working with gender and sexual minorities, and other diverse populations within New Zealand’ (NZCCP students, 2019, p. 15). Having too few staff members from diverse backgrounds means cultural labour is placed on minority students in psychology training to share with classmates and educate staff about their experiences (Hayward & Treharne, 2022; Johnson et al., 2021). Moreover, the inclusion of multiple worldviews in psychology is vital to empowering the voices of those who are excluded in psychological research. In 2021, a group of tauira Māori (Johnson et al., 2021) recommended the establishment of a bicultural psychology training curriculum so that ‘all those engaging with psychology in Aotearoa understand Te Tiriti o Waitangi and their responsibility to the biculturalism relationship – which does not solely sit with Māori to uphold’ (p.128). Psychology training programmes in Aotearoa are tasked with providing platforms for all students to reflect on the diversity of the population and offer solutions that take into account a Te Tiriti response that exists in relationship with other identities (Johnson et al., 2021).

Although overseas studies (e.g. Buboltz et al., 1999; Fish et al., 2023) have drawn attention to the monocultural nature of psychological research, little is known about how WEIRD psychology manifests in psychological research in Aotearoa. Therefore, we sought to provide some insight into how psychological research in Aotearoa responded to ethnic cultural diversity by examining the content of publications in Aotearoa psychology journals. The research questions that shaped this study were as follows.

RQ1: What proportion of articles published in Aotearoa psychology journals include a substantial discussion of ‘diversity’? The term ‘diversity’ was used to accentuate the wide-ranging minoritised identities that are rarely represented in the field of psychology in Aotearoa (Hayward & Treharne, 2022; NZCCP students, 2019).

RQ2: How is ‘diversity’ typically represented in Aotearoa psychological literature? Are there patterns of reporting that could be considered problematic?

Method

RQ1: In our efforts to capture research with an orientation toward biculturalism, multiculturalism and diversity, we conducted a content analysis of journal articles published in two prominent Aotearoa psychology journals: 1) Journal of the New Zealand College of Clinical Psychologists (JNZCCP; 152 articles between 2016 and 2021), and 2) New Zealand Journal of Psychology (NZJP; 225 articles between 2011 and 2021). We referred to the content analysis framework used by Buboltz Jr (1999) to examine the occurrence and representation of ‘diversity’ across journal articles. The first author was responsible for coding all articles and consolidating the coding framework through consulting with other research team members. The coding process began with screening the abstract of each article before reading the full text, followed by an in-depth analysis of articles with ‘diverse’ representation. A shorter duration was selected for JNZCCP, as we could not source earlier publications on the journal’s website. Except for editorial pieces, all types of articles were included in the analysis.

An article was manually coded as ‘diversity’ if it included a substantial discussion of issues relevant to minoritised identities, including indigeneity, ethnicity, religion, gender, migrants, refugees and rainbow. The ‘diversity’ category comprised studies that adequately covered at least one of three features: 1) a contextual background of minoritised groups (e.g. discussion of marginalisation history and social determinants of health); 2) the rationale (and culturally informed methodology) of undertaking studies with minoritised groups; and 3) the implication of study findings in promoting changes for minoritised groups. Articles that only considered diversity on a surface level were excluded; for example, studies that only recruited participants from diverse backgrounds or only included diversity as a ‘variable of interest’ and did not examine specific group differences.

RQ2: During the coding process, the first author made reflexive notes about the problematic framing of ‘diversity’ across articles. Reoccurring themes were written up as five problem statements, and the relevance of themes were discussed among the research team. Part of this paper was presented at the 2022 New Zealand Psychological Society Annual Conference for the Responses to Racism, Oppression and Discrimination Symposium. The construction of final themes benefited from feedback from conference attendees.

Results

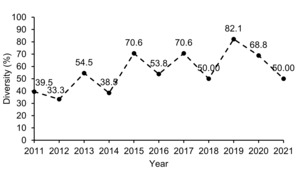

The proportion of JNZCCP and NZJP content categorised as diverse is shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. On average, three-fifths of articles published in NZJP had considered ‘diversity’. From 2016 to 2021, there was more diverse content in NZJP (62.6%) than in JNZCCP (22.7%). This difference may be attributed to the specific publishing requirements in NZJP, with all articles needing to meet at least one of the following scopes: a) include Aotearoa samples; b) discuss relevance of Aotearoa social and cultural context; or c) discuss the Aotearoa psychological practice. Despite a NZJP statement that all articles should include consideration of the applicability of the content for Māori, only 30.7% met this criterion.

Both journals had the highest representation of diversity in 2019 (82.1% for NZJP; 35.0% for JNZCCP), which was the year the March 15th Christchurch terrorist attack occurred. This may be partly attributed to the fact that NZJP published a special issue specifically addressing issues related to the attack. In this issue, authors discussed the white supremacy, racism and colonisation that have long affected Māori and minoritised groups in Aotearoa (Waitoki, 2019), as well as our roles as psychology researchers and practitioners to address the resultant health and social inequities (Mirnajafi & Barlow, 2019). There were other special issues that contributed to an elevated coverage of diversity. For example, the NZJP special issue entitled Indigenous Psychologies in 2017 included papers on bicultural practices in applied psychology (Pitama et al., 2017), and Māori well-being constructs such as whānaungatanga (Rua et al., 2017) and wairua (Valentine et al., 2017). Furthermore, the NZCCP special issue entitled What I Wish we had Been Taught in 2019 featured papers on the conceptualisation of kai as central to Māori wellness (Hale, 2019) and the call from NZCCP students (2019) to diversify the teaching of ‘mental health’ as a concept.

Our findings showed that psychology research in the two Aotearoa journals was limited in terms of the representation of diverse communities. Below, we provide examples of some of the issues found with the inclusion of diversity in the reviewed publications.

1. Inadequate Data Collection and Consideration of Ethnicity and Cultural Diversity

Example: Ideally, it would be useful to compare the response of X and Y to the programme. However, this was not possible because ethnicity data were not collected.

Such statements were relatively common. However, when researchers made these statements they were implying that diverse samples were either not recruited or when diverse samples were recruited, the mention of diversity was limited to demographic descriptions. The impact of inaction or choosing not to take active steps in including voices from minoritised groups in research can be seen as an example of white imprint (McAllister et al., 2022). This type of prejudice occurs when Eurocentric research is normalised and validated, whereby white epistemologies operate as a frame of reference to understand psychological characteristics of ethnic/cultural groups of diverse backgrounds.

2. ‘Controlling’ for Diversity

Example: X was negatively correlated with Y, after adjusting for relevant demographics.

Quantitative researchers often include diversity categories such as ethnicity and gender in their statistical models, but typically include these as simply control variables. The objective being to generate a one-size-fits-all conclusion, without fully understanding the cultural nuances and likely reinforcing hegemonic psychology. Language discourses are also important, since using terms such as ‘controlling’, ‘adjusting’ and ‘confounding’ adds to the view that culture and ethnicity are outside the everyday reality of human lives and that deeper engagement is not required. The ‘controlling’ of diversity in psychological research is not accidental; rather, it is a deliberate step for neglecting the impacts of a wide range of social, political and historical factors on minoritised groups.

3. No Contextualisation of Diversity

Example: X participants produced significantly higher scores than Y.

A few studies reported within-group differences for their samples, but those authors did not provide any explanations for the observed results. This left readers to make their own interpretation of the findings even though it is the responsibility of a researcher to conduct a thorough literature review and provide an informed discussion. The lack of informed discussion of such observed differences may perpetuate cultural stereotypes. These may be positive or negative, but either way, such stereotypes run the risk of ‘ranking’ cultures and social groups against each other.

4. Pathologisation of Diversity

Example: Not surprisingly, X reports lower well-being and life-satisfaction than Y. Notably, the well-being of X had remained relatively stable during this period, yet the well-being of Y had decreased substantially.

It was not uncommon to come across research that relied on negative statistics to depict psychological and health outcomes for minoritised groups, particularly among Māori. These studies commonly used measurements imported from the Global North that did not account for the local context. A social and cultural-justice lens needs to be applied when reporting on inequities for minoritised groups to avoid deficit-framing and victim-blaming.

5. Maybe…Further Research?

Example: Further research could be undertaken to make appropriate adaptations for the New Zealand population, including culturally appropriate adaptations for Māori and other ethnicities.

Some researchers chose to pass the responsibility for being attentive to diversity to others; this was especially common when a study had not recruited participants from minoritised backgrounds or examined within-group differences. A research project can move away from monoculturalism by including diverse representation on the research and authorship team that will engender visibility to historically silenced groups.

Discussion

Across papers published in NZJP and JNZCCP, a large number either did not adequately recruit minoritised groups or only considered diversity as a demographic data point. The lack of meaningful inclusion of minoritised peoples can result in practices and policies that are generically applied. The assumption of the WEIRD-default worldview in psychology research is that it can overlook full and active participation of minoritised participants, while still being considered meaningful and universal (Fish et al., 2023).

The need to defend the legitimacy of Indigenous and culturally diverse psychological knowledge stands against the backdrop of burgeoning evidence of white imprint in Aotearoa. First, notable inscriptions of white imprint are the under-representation of Māori, Pacific and Asian workforces in psychology (Scarf et al., 2019), and inequities in earning and promotion opportunities for Māori and Pacific academics (McAllister et al., 2020). A second inscription is the WEIRD ethnocentrism and monoculturalism in the psychology curriculum (Levy & Waitoki, 2015; Liu, 2019; NSCBI et al., 2018; Pomare et al., 2021). Although progress is being made with the recognition of te Reo Māori as an official language of this nation and the greater adoption of tikanga Māori in many institutions, there is also a push-back emerging. For example, in 2021, a letter drafted by seven senior academics at the University of Auckland (including a professor in psychology) openly dismissed the value of mātauranga Māori as a valid science. The authors of that letter defended their position with reference to the merits of rigour in scholarly debates. This defensive reaction by a group of senior academics reflects the dominance of a Eurocentric view and active attempts to suppress mātauranga Māori in Aotearoa (Waitoki, 2022).

Indeed, psychology academics and researchers in Aotearoa are ethically required to have regard to the principles of the Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Macfarlane et al., 2011). These were interpreted by the Waitangi Tribunal (2019) in the Hauora claim (Wai2575) as requiring the Crown to implement the principles of partnership (balances the influences of kāwanatanga and tino rangatiratanga), active protection (empowers Māori tino rangatiratanga and Māori right to autonomy), equity (guarantees Māori freedom from discrimination and eliminates barriers for Māori to access care) and options (affirming the right for Māori to choose their social and cultural paths). A meaningful commitment to Te Tiriti and the recognition of the multicultural nature of the population requires that both are centralised in the scope of all psychology journals in Aotearoa. In 2023, JNZCCP inserted a new journal statement that welcomes potential authors to consider ‘implications [of submissions] for New Zealand’s indigenous Māori people, according to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi’.

Under the core competencies for the practice of psychology (New Zealand Psychologists Board, 2018), psychologists are required to demonstrate cultural competency by ‘having the awareness, knowledge, and skill to perform a myriad of psychological tasks that recognises the diverse worldviews and practices of oneself and of clients of different ethnic/cultural backgrounds’ (p.16). The findings from our review indicated more needs to be done to bridge the cultural knowledge gap that currently exists in psychological research, and for greater inclusion of perspectives and experiences from minoritised groups.

Our intention in reviewing NZJP and JNZCCP content was to again highlight the issue of the dominance of white epistemologies and the need for culturally competent and equity-focused research. We are reminded that any attempts to resolve challenges for Indigenous and minoritised ethnic groups from within white epistemologies are likely to do more harm than good (Fish et al., 2023; NSCBI et al., 2018). Achievement of Te Tiriti aspirations needs to begin by embedding the wisdom that lies within mātauranga Māori and culturally diverse knowledge sources across all areas of psychology. Western bodies of knowledge need to be recognised as their own distinct cultural stream that cannot be transferred directly to another culture. Furthermore, Indigenous paradigms that value relationship, collectivism, reciprocity and epistemological pluralism are to be viewed in parity with positivist and scientific approaches favoured in Western knowledge (Ansloos et al., 2022). That said, in some instances, there is the potential to blend with culture-specific streams of knowledge to offer more responsive and relevant practices in psychology (Macfarlane & Macfarlane, 2018). In Te Tiriti article three (mana ōrite), everyone residing in Aotearoa is guaranteed equitable treatment and outcomes (Waitangi Tribunal, 2019). Therefore, honouring Te Tiriti also requires the recognition of the knowledge sources that have been historically marginalised in psychology and supports leadership from minoritised groups in challenging the monocultural nature of psychology. The affirmation of diverse knowledge streams is also a step towards redressing the unequal power dynamics for minoritised groups in conducting research, securing research grants and publishing in ‘high impact’ journals.

Although providing a useful overview, the present study is not without limitations. First, our measure of ‘diversity’ meant that articles could have covered multiple communities (e.g. indigeneity, ethnicity, religion, gender, migrants, refugees and rainbow/LGBTQIA+) or only a single community. While this approach has strength given that many of these communities may intersect, it may be that our measure of diverse content over-estimated content coverage from specific communities (e.g. rangatahi). Second, the ‘diversity’ category used in this study was unlikely to have captured the full breadth of minoritised identities within psychology. It is not the intention of this paper to speak for all diverse groups; rather, this paper sought to evoke commitment to redistributive justice in changing the field of psychological research (Ahmed, 2006). Third, although we assessed the diversity of articles, we did not collect information on the diversity of authors. It is likely that whether specific communities are acknowledged and how they are discussed in an article is related to their representation among the authors. However, unlike article content, the diversity of authors can only be assessed when adequate demographic information is collected. Much like university affiliations, it may be beneficial for journals to provide authors with the option of providing this information with their article (e.g. Māori authors listing their iwi). However, reflecting on our discussion above, it is also important to acknowledge that many authors may not feel safe providing this information.

Somewhat related to our second point, articles we classified as diverse may still fall short in other areas. For example, as noted above, the diversity of NZJP articles peaked in 2019, in part because of the special issue that followed the March 15th Christchurch terrorist attack. When psychologists respond to such tragic events, it would be beneficial to include more voices and perspectives from the affected communities. Finally, this paper did not scrutinise Aotearoa psychological research published in overseas journals. Given that overseas journals (particularly Anglo-American-based journals) have less stringent requirements around the discussion of indigeneity, diversity and minoritised identities, we speculated that such publications may have minimal consideration of the bicultural and multicultural context in Aotearoa.

Conclusion

Over the last few years, a number of international psychology bodies, including the American Psychological Association (2021), Australian Psychological Society (2017) and the British Psychological Society (2020) have issued apologies to indigenous and racialised communities for failing to challenge racism and racial discrimination. These apologies included a commitment to address the oppressive psychological science that helped to create, express and sustain a research landscape conforming with white racial hierarchy. To prevent such symbolic apologies from going down in history as performative, genuine and tangible actions needs to be undertaken to transform monocultural research practices in psychology. Psychology bodies in Aotearoa, including the Board, NZPsS and NZCCP, are currently engaging in the process of unpacking their role in marginalising Māori and minoritised groups and their knowledges. The monocultural nature of psychology does not only affect Māori as tangata whenua, but also other groups that are consigned a minority status through multiple (intersecting) structures of oppression (e.g. heteropatriarchy, racism and cisgenderism). Our findings assert that Aotearoa psychology research is not excluded from the systemic privileging of knowledge sources originating from WEIRD ethnocentrism. Through this article, we offer insight into how researchers can be Te Tiriti-focused and culturally responsive to advance the psychology discipline to be more relevant for Aotearoa.

Acknowledgements

The present research constitutes part of a larger WERO project (Systemic Racism in Health Education, Training, and Practice) that focuses on the three dimensions of racism in psychology in Aotearoa: its costs, systems and the potential responses that exist. WERO was funded by the MBIE Endeavour Fund in 2020 (UOWX2002).

Ethical requirement

No ethics approval was sought for this study as it did not involve human participants. The research solely focused on journal articles published in two Aotearoa psychology journals that are available in the public domain..